The project I am currently working on examining, in part, the connections among my various family members. It's fascinating to me that we all know each other so well, and yet at the same time don't know each other at all. What connects us as a "family"? A. Hope Jahren, currently a professor of biogeochemistry at the University of Oslo, recently published an essay in The New York Times titled

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/07/opinion/sunday/my-fathers-hackberry-tree.html?_r=0

"My Father's Hackberry Tree". In it, she describes a connection to her father that arose from her research work:

"...In 1993, my father collected hackberry fruits for me. My task that year was to observe the development of the seed over the course of the growing season, and I had earmarked several trees in South Dakota for that purpose. During a rare visit home to neighboring Minnesota, I saw with new eyes the fine specimen of C. occidentalis that graced the southwestern corner of my parents’ property.

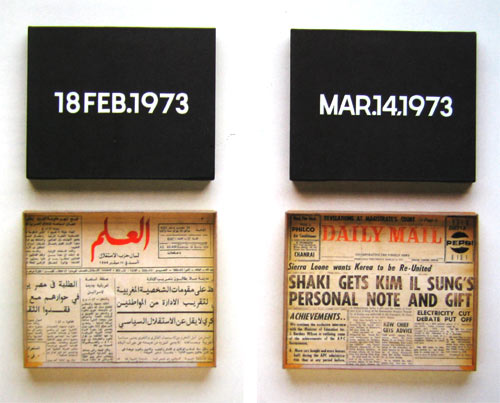

I asked my father if he wouldn’t mind pulling off a few fruits every week throughout the summer, and he obliged. From May through September, he visited our hackberry tree twice each day, carefully recording the weather conditions, and also sampling, first flowers, then green fruits, then ripe, then withered, all placed into small plastic vials. Hundreds and hundreds of fruits — each week’s harvest wrapped in a sheet of paper describing its yield.

... (My) father spent the better part of his 70th summer observing a single tree, and in the end, gave me a hundredfold more than what I had asked for.

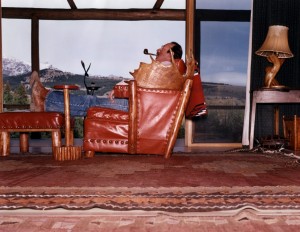

My father can no longer write. He is 92 now, and he cannot make his hands work. He cannot walk, or even stand, and he can barely see. He is not certain what year it is, but he is sure that I am his daughter, and that my brothers are his sons, and he treats us just as he always has...

When I visit him these days, we sit in the same house that I grew up in, but we don’t talk about science anymore. ... (We) talk about poetry instead...

As with many Midwestern families, great distances pervade our relationships — both literally and figuratively. We never really talk to each other; instead we box up our hurts and longings and store them for decades, out of sight but not forgotten.

... This year my father and I have spent (the summer) inside, reading...

In the fading light, we offer each other words that were carefully written by dead strangers, because we know them by heart. We also know that children eventually leave. Even when they do come home, there’s always the end of the day, of the week, of the summer, when they fly away to the other side of the world, off to a place where you cannot follow.

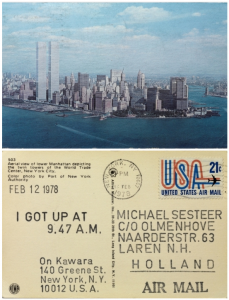

This month I am leaving Minnesota, and the United States, relocating yet again, to build a new lab and start over a fourth time. Compared with my previous moves, I am taking very little with me. The dead fruit of my early career has now been discarded. Instead, I carry in my luggage a delicate pile of paper. It is the small bundle of notes written in my father’s handwriting that I recovered from the box of hackberries he collected.

The notes are precious because they constitute proof — proof that my father thought of me every single day and must still do so. Proof that I am his, our shared last name written on every page. Proof that no one in the world knows that tree the way he and I do.

Our hackberry tree still stands, tall and healthy, near the western edge of Mower County. It should outlive both of us, growing stronger and greener even as we inevitably wither and fall. The tree will remain in my parents’ yard, and the notes describing what it was like 20 years ago will go with me, though its fruit will not.

I am taking with me only what I can’t live without, and the utility of these letters is clear. This collection of papers, filled exclusively with symbols and dates and botanical terms, is all of the things that my father and I have never said."

How beautiful that a collection of simple scientific data can make such a profound connection with a loved one. This task that was performed daily for a summer left behind evidence of that love, of the fact that the father thought every day of his daughter, and performed a service on her behalf. The notes that Jahren's father made say "I love and respect you." in a different way than the words themselves, and which is profoundly affecting.

Members of a family sometimes express attachment and affection for one another in such subtle ways that they can be essentially invisible or are not seen for what they are. It is this sideways approach to familial relationships that I am examining right now. What do we discover about our families and our selves when we look for evidence of love and connection in the less obvious places, in the places where links are there, but lie undetected? Trying to answer this question is requiring me to think quite differently than I have in the past about how to portray these issues visually.