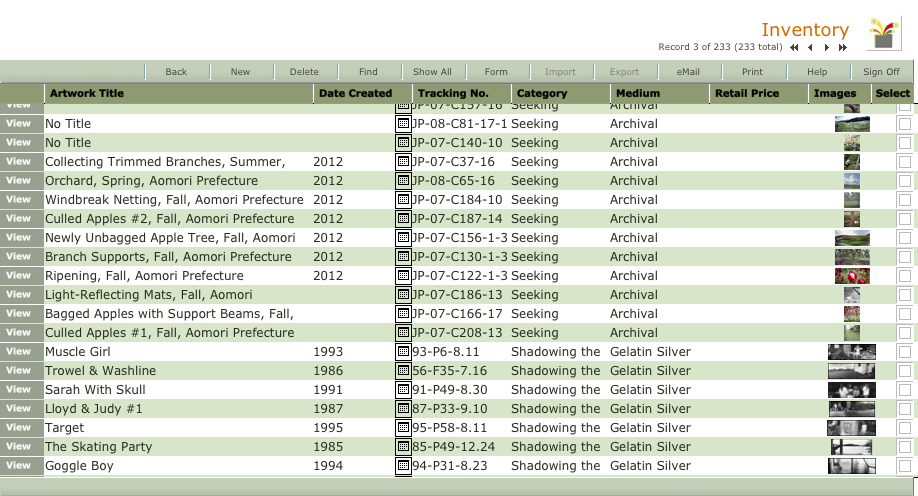

When my father died, he left behind a collection of over 25,000 Kodak Kodachrome 35mm slides that he had taken between 1945 and 1996. It wasn’t until the mid-’90’s that he went digital, as until then, digital cameras could not capture the kind of color and information that Kodachrome film could. Being the super-organized person he was, he had edited the slides down and stored them in carefully labeled slide carousels so that he could show them at family gatherings.

By the time he passed, I didn’t really know what those carousels contained, as it had been many years since he had shown them. I proceeded to go through every single one, curious to learn what I would find. I quickly realized that my father was interested in two major subjects as a photographer: the natural world and his family.

But there were three slides I came across that shocked me. I literally gasped when I saw them.

Taken in 1982, these three pictures were so unlike any of the others, that I saved them for the treasures they are. Because he appears in all three, they were most likely taken by my mother (at least two of them were, including the one of the left; the last one below is debatable), in locations that are unknown to me.

These pictures are the technical antithesis of the kind of photograph my father sought to achieve, which was to have sharp focus and clear, rich colors. The camera used to take these three was clearly malfunctioning, at least on two of them, and the focus is off. They are also anomalies in terms of content, as he was of the “What you see in the photo is exactly what was in front of my camera.” persuasion. Visual ambiguity in any form was to be avoided. So why did he save these three photographs, which suffer from what would have been to him so many technical and aesthetic flaws?

Did he save them simply because he had no other slides from those days and locations? Why did he save a picture in which the only identifiable thing in it is his hand? (seen on the right) Most of the information in this photograph is indecipherable, and I can’t make out what his hand might be reaching for.

What did the silhouette and reflection in the photograph seen below mean to him? It seemed crazy this last photo is so similar to the work I am doing now (see Witness Marks). It felt like my father was sending me a message of some kind, but what that might be, I have yet to discover. All I know is that that particular picture connected us in some visceral way.

I ultimately saved 2,700 of the family photo slides from all those that he had taken. I value them highly, as they depict five decades of our family history that otherwise would have been lost. But it is these three slides that my creative self is most fascinated by. It’s almost as if my father saved them just for me, knowing that eventually I would find them and wonder why…