I have written a number of posts about how the presentation of artwork can affect the viewer's perception of that art. The other day I ran across a fantastic video that speaks to the same issue as it relates to food. "Tasteology" is a series of four videos that address the issue of why food tastes the way it does. The first three episodes focus on the source of the raw ingredients, how they are prepared, and how they are stored. The final episode, found below, examines how the presentation and environment in which food is eaten affects our perception of its flavor and textures. From the room and the plating to the ambient sounds and lighting, this video speaks to an issue that all artists should think more about when considering how to present their work. I loved it! [embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0CDsifeDf-c[/embed]

research

Tracking Family Connections

The project I am currently working on examining, in part, the connections among my various family members. It's fascinating to me that we all know each other so well, and yet at the same time don't know each other at all. What connects us as a "family"? A. Hope Jahren, currently a professor of biogeochemistry at the University of Oslo, recently published an essay in The New York Times titled

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/07/opinion/sunday/my-fathers-hackberry-tree.html?_r=0

"My Father's Hackberry Tree". In it, she describes a connection to her father that arose from her research work:

"...In 1993, my father collected hackberry fruits for me. My task that year was to observe the development of the seed over the course of the growing season, and I had earmarked several trees in South Dakota for that purpose. During a rare visit home to neighboring Minnesota, I saw with new eyes the fine specimen of C. occidentalis that graced the southwestern corner of my parents’ property.

I asked my father if he wouldn’t mind pulling off a few fruits every week throughout the summer, and he obliged. From May through September, he visited our hackberry tree twice each day, carefully recording the weather conditions, and also sampling, first flowers, then green fruits, then ripe, then withered, all placed into small plastic vials. Hundreds and hundreds of fruits — each week’s harvest wrapped in a sheet of paper describing its yield.

... (My) father spent the better part of his 70th summer observing a single tree, and in the end, gave me a hundredfold more than what I had asked for.

My father can no longer write. He is 92 now, and he cannot make his hands work. He cannot walk, or even stand, and he can barely see. He is not certain what year it is, but he is sure that I am his daughter, and that my brothers are his sons, and he treats us just as he always has...

When I visit him these days, we sit in the same house that I grew up in, but we don’t talk about science anymore. ... (We) talk about poetry instead...

As with many Midwestern families, great distances pervade our relationships — both literally and figuratively. We never really talk to each other; instead we box up our hurts and longings and store them for decades, out of sight but not forgotten.

... This year my father and I have spent (the summer) inside, reading...

In the fading light, we offer each other words that were carefully written by dead strangers, because we know them by heart. We also know that children eventually leave. Even when they do come home, there’s always the end of the day, of the week, of the summer, when they fly away to the other side of the world, off to a place where you cannot follow.

This month I am leaving Minnesota, and the United States, relocating yet again, to build a new lab and start over a fourth time. Compared with my previous moves, I am taking very little with me. The dead fruit of my early career has now been discarded. Instead, I carry in my luggage a delicate pile of paper. It is the small bundle of notes written in my father’s handwriting that I recovered from the box of hackberries he collected.

The notes are precious because they constitute proof — proof that my father thought of me every single day and must still do so. Proof that I am his, our shared last name written on every page. Proof that no one in the world knows that tree the way he and I do.

Our hackberry tree still stands, tall and healthy, near the western edge of Mower County. It should outlive both of us, growing stronger and greener even as we inevitably wither and fall. The tree will remain in my parents’ yard, and the notes describing what it was like 20 years ago will go with me, though its fruit will not.

I am taking with me only what I can’t live without, and the utility of these letters is clear. This collection of papers, filled exclusively with symbols and dates and botanical terms, is all of the things that my father and I have never said."

How beautiful that a collection of simple scientific data can make such a profound connection with a loved one. This task that was performed daily for a summer left behind evidence of that love, of the fact that the father thought every day of his daughter, and performed a service on her behalf. The notes that Jahren's father made say "I love and respect you." in a different way than the words themselves, and which is profoundly affecting.

Members of a family sometimes express attachment and affection for one another in such subtle ways that they can be essentially invisible or are not seen for what they are. It is this sideways approach to familial relationships that I am examining right now. What do we discover about our families and our selves when we look for evidence of love and connection in the less obvious places, in the places where links are there, but lie undetected? Trying to answer this question is requiring me to think quite differently than I have in the past about how to portray these issues visually.

Piezography Workshop for Black & White Printing

My current project, titled The Thread in the River, is a mix of photographic media: film, digital, and video. I am creating a number of series, some of which are going to be printed in black and white. My Tears of Stone: World War I Remembered project was printed with Piezography software and inks back in the early '00's, so I knew that that is the method that I want to print this new b&w work with. But a lot has changed since then and I knew that I needed a total reboot. So I signed up for one of the New Piezography Workshops at Cone Editions Press in East Topsham, Vermont, and traveled there last month for it.

With participants from China, Japan, Canada and the US, it was a truly international experience. Throughout the workshop, Jon Cone, Walker Blackwell, and Dana Hillesland each filled us in on different aspects of the process, including information about how to prepare image files, how the software works, printer setup and maintenance, and far, far more. We were able to print on a large assortment of papers using 5 different inksets. They did a lot of one-on-one work with each of us, as we all had come there with different needs and agendas.

In addition, I got to see Cathy Cone's photographic work, which is gorgeous and evocative. At the end of the last day, we spent some time at the waterfall nearby, then walked back to share wine, beer, and stories. It was a beautiful summer day and a fitting end to a fantastic experience, surrounded by people for whom craft is important. For anyone who is serious about fine digital black & white printing, Piezography is the way to go.

My Photographic Archives- What to Do With Them? (Part 4)

Because I've recently been thinking and writing a lot about what happens to artwork when an artist dies (don't worry, I'm perfectly healthy), I've been researching why artwork gets archived, how it gets organized, recorded and stored, and things to think about when creating a plan for one's archives. Finding solid helpful information was challenging at first. It wasn't until I started using search terms like "estate planning for visual artists" that I began finding items that I felt could usefully guide me towards finding answers to my questions.

What follows are a few of the best sources I could find:

Etched in Memory: Legacy Planning for Artists (An online resource that has a ton of resources listed on this topic.)

A Visual Artist's Guide to Estate Planning

Artists' Studio Archives website (This has a great page of handouts from "how to" workshops that they have offered.)

Artist's Estates: Reputations in Trust (This is a book that outlines what happened to a number of 20th C. artists' works after they died.)

Estate Planning Guide and Career Documentation Workbook (from the Joan Mitchell Foundation- both were updated in Feb. 2015)

After reading a number of the above items, I'll be honest- it's enough to make your head explode, even for someone like me who is crazily detail-oriented. I now realize that, for artists, there are two major things to think about when it comes to estate planning: 1. your artwork, and 2. everything else. Holy crap! At least I've got a fairly up-to-date inventory of my artwork, so that's a start.

Be that as it may, I'm very clear that I do NOT want to burden my family with having to figure out what to do with my artwork once I am gone. Given that, I have to get my act together in order to create a plan that relieves them of that task. I'm glad to now have some guidance for doing that.

My Photographic Archives- What to Do With Them? (Part 3)

I decided to do some research on the nature and purpose of photographic archives recently, and came upon a blog post titled "What Does a Photograph Archivist Do?" by Marguerite Roby, the photographic archivist for the Smithsonian Institution Archives. In it, she described her job as follows: "The images that make up the collection in my particular care are memories of artifacts, exhibits, events, and people that tell the story of this institution. To me, memories are like undeveloped film. They become useless when they are not articulated or developed in a way that makes them meaningful to an audience. Memories are also prone to distortion over time, so it’s paramount to record them so that the stories they tell become a resource for future generations... It is my job to see to the preservation of the physical images as well to capture and preserve the meaning behind them so they remain relevant over time."

That's one of the best explanations I have found for why archives exist. They serve to keep the record straight for future generations. They provide context for those people in the future who seek to understand the past. They provide a connection to who and what has gone before. And from that standpoint, it doesn't matter if you are someone as important in their field as Bob Dylan, or someone whose name will never be known to the masses. Everyone plays a role in the fabric of life, and preserving those stories is important.

I also came across a list of criteria to consider when thinking about what to include in an archive:

- The purpose of the archive

- The uniqueness of an item

- The quality of an item

- The amount of documented information about an item that is available

- Whether an item is too private or personal to include

Those points can help serve as guidelines to answering some of the questions that I have had about archiving my artwork, and the best place to start is to try figure out what the purpose of my archives would be.

Dayton Art Institute Artist's Talk

Tomorrow (Thur., Sept. 17) I'll be giving an artist's talk about the "Tears of Stone" show currently on exhibit at the Dayton Art Institute. The show is up through Sunday, October 4. Here's a link with more information about the lecture, which includes a short video of me talking about one of the pieces in the show.

I've spent the past few days putting this talk together. In brief, it will include information about the research I did for the project, the technical aspects and challenges of shooting it, and I'll be reading excerpts from my field notebooks about experiences I had while working on the project. I'm really thankful for the opportunity to do this- it's been a while since I've made a presentation about this work, and it's nice to get back to it.

Photographic Archaeology

A character in "A Forgotten Poet", a story by Vladimir Nabokov, writes, "If metal is immortal then somewhere

there lies the burnished button I lost

upon my seventh birthday in a garden.

Find me that button and my soul will know

that every soul is saved and stored and treasured."

The same could be said for photographs. We take them and put them away somewhere, in a drawer, in a shoebox, on our computers, or in the Cloud. All too often, we proceed to forget about them.

Every once in a while, we happen to come upon these treasures from the past. When we do, our gaze falls upon them and memory is reawakened. Emotions bubble up and time shifts somehow. Going through old photographs is like participating in an archeological dig. We sift through layers of the past, trying to make connections between the history being revealed and the present.

It is inevitable that, in this process, questions will arise that cannot be answered. But by asking those questions, we learn something about our selves, and the past lives again. Photographs are not the only artifacts that have the ability to generate these sensations, but they do it in a way that is unique to the medium.

This has a direct bearing on the creative work I am doing now, in which I am sifting through my photographic archives and discovering much in the process. I'm still editing all of this, trying to make sense out of the thousands of images I am looking at. Stay tuned to what emerges!

This has a direct bearing on the creative work I am doing now, in which I am sifting through my photographic archives and discovering much in the process. I'm still editing all of this, trying to make sense out of the thousands of images I am looking at. Stay tuned to what emerges!

Thoughts on Influences

I saw a show a few months ago that made me angry. When I realized that I was angry, I stopped to ask myself why. The subject matter of the photographs was landscapes, the pictures were impeccably printed and presented cleanly. Straight photography at its best. At first glance, it seemed absurd that I would get angry about work like this. But then it dawned on me that this particular work belonged to a long and powerful photographic tradition of Modernism that still resonates today. When I first became involved with photography in the 1980's, this approach to the medium was everywhere. It was the kind of photography that got the most accolades and attention from the mainstream media and the public. It was what was (mostly) taught in schools. At the same time, the Postmodern approach to photography was extremely popular in galleries and museums, and that was mostly what art critics were championing.

I didn't feel at home in either camp. The issues that Postmodernism examined were not the kinds of things that I was interested in. But neither was I comfortable with the kind of approach that had made the Modernists so successful in the early to mid 20th century, particularly as it related to subject matter. I found both approaches, with a few exceptions, to be relatively dry spiritually and emotionally. They held no magic for me, and didn't speak to me in a way that I could respond to.

Seeing the exhibit of landscape photographs mentioned above generated anger because it made me realize just how powerful an influence the Modernist male photographers in particular had on me at that time. The show represented everything I don't want to be as an artist. Seeing this work made me realize that I have been constantly fighting off the voices that were most dominant during my photographic coming-of-age. A lot of my creative struggles have sought to inject passion, emotion and narrative into my subject matter, to make photographs that speak to people personally, to make them relatable.

The takeaway? Influences can not only be positive, they can also be negative.

But the fact that they can be negative is not necessarily a bad thing. In my case, it has forced me to define for myself exactly what I want my creative voice to be. I recognize that parts of my process are more Modernist than not, but feel that the content of most of my work departs in large part from that mold.

The Artist vs. The Creative Entrepreneur

I read a great article in this month's edition of The Atlantic magazine titled "The Death of The Artist and the Birth of the Creative Entrepreneur", by William Deresiewicz. In it, he states that "the image of the artist has changed radically over the centuries. What if the latest model to emerge means the end of art as we have known it?" He starts his discussion by pointing out that artists were initially seen as artisans. That evolved into the artist as genius, then later the artist as professional. The model that is currently emerging in the early 21st century, according to Deresiewicz, is that of the "creative entrepreneur", someone who acts not only as the creator, but who also markets, bills, advertises, etc., instead of having someone else (ex. an employer) do it for her/him.

Deresiewicsz goes on to suggest how the artwork itself might change as a result of this shift. Having taught a class in fine arts professional practices for many years, and having experienced this shift first hand as an artist, I have to say that I agree with the author's perceptions about the change that is going on for artists today. It is like being on shifting sands all the time, as the way the game is played seems to change constantly, albeit in sometimes subtle ways that are not immediately comprehended.

Artists I Like- J. M. W. Turner

I first became aware of the power of art when I was in my early twenties. Prior to that, I of course had seen art before, but I had never thought much about it. But when I started taking art and music history classes, I began to realize that a sculpture wasn't just an inanimate 3D object, a building wasn't just a form that provided shelter, a musical piece wasn't just a bunch of notes strung together, and a painting wasn't just a canvas with paint on it. The idea that an artwork could contain an entire universe of thought and meaning was a revelation to me, and I dove with great enthusiasm into exploring as many different types and eras of art as I could in order to learn more. It's been interesting to see which artists have risen to the top of my own personal list of favorites over the years. One of the painters who rocketed to the top and has stayed there is 19th Century English landscape painter and printmaker J. M. W. Turner. Looking at his seascapes, in particular, is like listening to a Beethoven symphony.

No one else used paint the way he did at that time. Very few painters saw and conveyed light in the way he did. His paintings exude energy and vibrancy- they are almost alive in their shimmering atmospheric presence. Many of his paintings contain historical references, both ancient and contemporary to his time, but in ways that are visually atypical for a 19th Century painter.

I have been thinking a lot about his work recently because a film, "Mr. Turner", has come out that has Turner as its main character and which has been recommended to me by many friends. (Note to self: Put that on my list of films to see when it comes to town...)

The New York Times published a review of the film by critic A. O. Scott, the last three sentences of which perfectly sum up one of the reasons that I make art:

"By the end [of the film], we may not be able to summarize Turner's life, explain his paintings or pass a midterm on British history. But we may find that our knowledge of all those things has deepened, and the compass by which we measure our own experience has grown wider. Only art can do that, and it may be all that art can do."

And isn't that amazing??!! That an art object can lead to that kind of self-knowledge??!! It's that kind of knowledge that not only enriches us, but that can lead us to act, and therefore live more meaningful lives. Any artist whose work can do that for others is worth knowing about. And because your work has done that for me, I thank you, Mr. Turner.

Interview Published in AEQAI

ÆQAI (pronounced ‘I’ as in ‘bite ‘ and ‘qai ‘ as in ‘sKY’ ) is a Cincinnati based e-journal for critical thinking, review and reflective prose on contemporary visual art. An interview titled "Jane Alden Stevens: Photography in Motion" authored by Laura A. Hobson was recently published in the November, 2014, edition of AEQAI. The article includes images from various bodies of work, a discussion about my teaching career, and covers a number of issues including the role that feminism played in my classroom, mentors, technical changes in the field and my approach to art-making.

Many thanks to editor Daniel Brown for including me in this issue!

Making the Familiar Strange

In my last post, I quoted a sentence that was in reference to Seamus Heaney's poems: "He takes the familiar and makes it strange." This sentence describes perfectly what I am trying to do in my current work. Because this is no easy thing, I have been thinking a lot about what it is, exactly, that can make the familiar into something strange or unsettling. In researching this, I came upon this blog entry by Pat Thompson, Professor of Education at the University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom. She writes about how de-familiarization is about "seeing things differently, and understanding them differently." The ability to convey to viewers/readers/listeners this different understanding of something familiar is key.

Musicians are challenged by this concept any time they do a cover version of a well-known song. Sometimes they produce a more-or-less faithful rendering of the original, but other times, the cover version causes the listener to hear something in the song that had been previously unknown. I can think of two examples that illustrate this perfectly.

The first is Whitney Houston's "How Will I Know". Her original was a perfect piece of pop confection that speaks to the angst of young women just starting on their journey of negotiating relationships. Her a cappella version, although not a cover version by someone else, reveals the concerns of a grown woman who has already lived a life and experienced failures in love.

The second example is Chris Cornell's cover of Michael Jackson's "Billie Jean". There is a gritty, desperate aspect to Cornell's version that was absent for me in the original. I had become complacent about the song until I heard Cornell's version, which caused me to relisten to Jackson's original and rethink what i thought I knew about it. I found far more angst and anger there than I had heard initially.

In both cases, the experience as listener was revelatory, exciting and..... strange. You are familiar with the subject, but because it is being presented to you in a way that is different from the norm, you feel like you don't know it at all. It is this sensation that I am aiming for in the photographs I am creating right now.

PhotoEye Blog Interview

I was recently interviewed about the Seeking Perfection project for the PhotoEye blog. Here's a link to the interview. It's always a struggle to put into words the thought processes behind my work, but always a rewarding experience. This is because I find that I learn something different about my work and about my approach to making pictures when I either talk about it or write it down, than when I simply think about it. I really enjoy that sense of discovery as it helps to move me forward, even when I have long since completed a project.

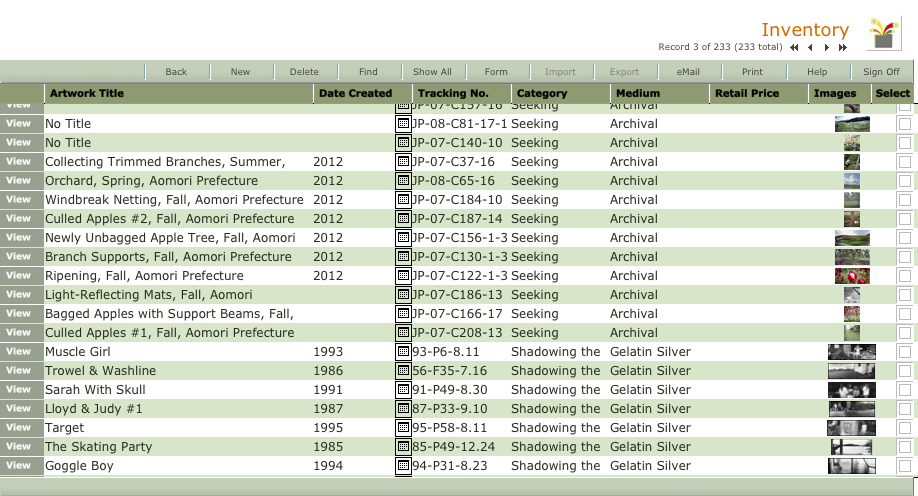

Inventory Database for Artists

I've been a pretty organized person over the years when it comes to my art career. But when it comes to keeping track of everything, I finally realized how great it would be if I could keep most records in one place.

I've got folders on my computer that contain Word docs, Excel spreadsheets, FileMaker databases, etc., and I'm constantly having to dig through those files in order to cross reference the information in them. In addition, I've been using Excel for my inventory database, but have been frustrated by its limitations. The following images give a visual of what I'm talking about:

You can imagine how many files are contained within these folders. Kind of crazy.

I was aware of inventory software for artists such as Flick! and eArtist, but after looking into them further, decided that they weren't for me.

Then I discovered GYST software. GYST stands for "Get Your Sh*t Together".

Created by artist and educator Karen Atkinson, GYST does far more than even the most fanatically organized person could ever need, which is one reason why I love it. Here's a screenshot of an individual artwork record in GYST. Note that you can add detailed information into any of the blue tabs found in the middle of the window:  And if you want to look at your entire database of artwork, it will show up as a list like this:

And if you want to look at your entire database of artwork, it will show up as a list like this:  You can pick and choose which features you want to use in GYST. Not only will it allow you to keep your inventory up to date, it will also help you keep track of any proposals you may have out, artist's statements, your resume, contacts, research notes, billing, etc., and it's all found in one place on your computer. Heaven!

You can pick and choose which features you want to use in GYST. Not only will it allow you to keep your inventory up to date, it will also help you keep track of any proposals you may have out, artist's statements, your resume, contacts, research notes, billing, etc., and it's all found in one place on your computer. Heaven!

Check out the GYST blog, as it's a great resource for professional practices information.

I should add that my only beef with any of the above-named inventory databases is that they are not particularly intuitive or user-friendly, so there is a definite learning curve involved at first. If someone could come up with one that is relatively easy to use from the get-go, I would not hesitate to use it.

A Book on Wood Carving

In the March 16th issue of the Economist, I read a review of a new book by woodcarver David Esterly. The title of the book, The Lost Carving: A Journey to the Heart of Making, immediately caught my eye and the review made me want to read it. Here's the part of the review that spoke to me most: (The book) "...is a meditation- on "beauty, skill nature, feeling, tradition, sincerity", all now art-world anachronisms, he fears. But above all, it is a song to his medium, the wood itself, its grain, the way it answers to the blade, the conversation to be had with it. "Making" is the word in Mr. Esterly's title, and it is the nub of his book. He is in love with the physicality of his art, the flowing together of hand and brain, of chisel and creativity. The idea that the artist should both master and be mastered by the medium clearly fascinates him.

Lovely! Will have to read it ASAP.

"Daylight" Books & Magazine

Anyone interested in photography that explores the elusive boundaries between conceptual fine art work and documentary should check out Daylight, which is a "non-profit organization dedicated to publishing art and photography books." Daylight's writers include Kirsten Rian, whose ongoing "Alphabet of Light" articles count among the most eloquent, thoughtful writing on photography that is being done today.

A talented writer/painter/musician/photographer, Rian makes connection between the

photographer, the photograph and our internal and external world in ways that are extraordinary. I always end up feeling like I have learned something new after reading one of her pieces. A gift to the world....

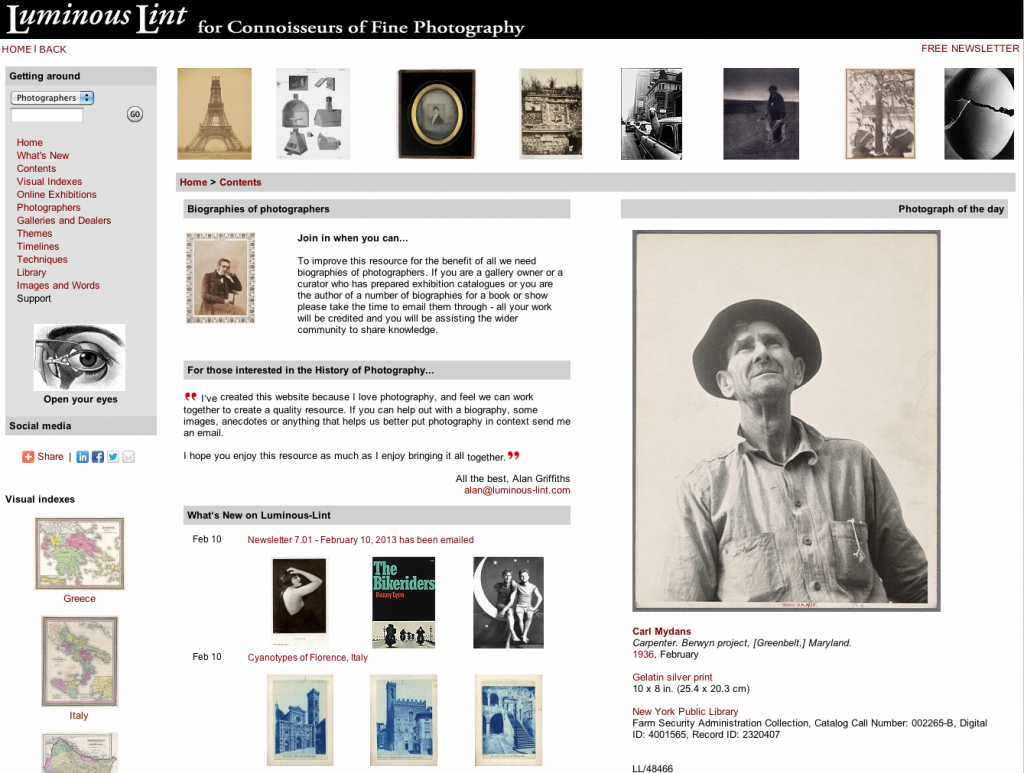

Photography Database- Luminous Lint

One of my favorite databases on photography is Luminous Lint. It is unlike so many other databases, in that it is searchable in so many different ways- by photographer, technique, theme, date, geography... it's just amazing. It contains not only images, but short bios of photographers, and has lots of galleries that allow you to view these photographs in different contexts. It also contains images that you would rarely see in galleries or museums, plus articles on unusual topics such as non-canonical photography, sequences and series, and fabricated realities.

The site's creator, Alan Griffiths, is completely enamored with photography, and it shows! It is a fantastic research tool.

Art Photo Index

I'm honored to have been invited to be a part of the Art Photo Index, an online searchable database of art and documentary photographers and their work. It currently includes close to 3,000 photographers representing 85 countries. Check it out!

Thoughts on How Creative Interests Change Over Time

Having gone to the "Emmet Gowin and His Contemporaries" show up in Dayton recently inspired me to do a little more research on him. I came across an interview with him by Sally Gall (a great photographer in her own right) that appeared in Bombsite magazine back in 1997. When asked by Gall about his transition from family pictures to landscapes, Gowin said:

EG: "...I always knew that it wasn’t going to last. You can’t be an artist and have your identity reside in only one thing. The thing that you master will become a stranger to you, and you will outlive it or you will need to live into something else. You will always need to be educating yourself to the complexity of your feelings as they grow, and you don’t want to do something twice, really.  Everything that makes you an artist in a sense is the way things are understood; how they fit together in ways that have not been understood before. How can you discover the inherent value that’s hidden in things that you haven’t yet seen? It’s in that sense that you want to do something new. And you know that it’s chance that’s going to put those things together. Only chance can bring together new combinations in a way that is revolutionary. No one ever discovered anything really important intentionally."

Everything that makes you an artist in a sense is the way things are understood; how they fit together in ways that have not been understood before. How can you discover the inherent value that’s hidden in things that you haven’t yet seen? It’s in that sense that you want to do something new. And you know that it’s chance that’s going to put those things together. Only chance can bring together new combinations in a way that is revolutionary. No one ever discovered anything really important intentionally."

SG: "You can’t will it into being."

EG: "If there were no problem there would be no discovery.  But also, there has to be the confrontation with something inexplicable, something you didn’t intend to do and that has so much presence you say, “Okay, I don’t expect you to go away, but I don’t know what you’re good for.” Chemistry and the sciences are full of this kind of thing. And that’s what’s underneath the creative life for artists, how to grasp the interrelationships that exist in the world in a way that hasn’t been done before."

But also, there has to be the confrontation with something inexplicable, something you didn’t intend to do and that has so much presence you say, “Okay, I don’t expect you to go away, but I don’t know what you’re good for.” Chemistry and the sciences are full of this kind of thing. And that’s what’s underneath the creative life for artists, how to grasp the interrelationships that exist in the world in a way that hasn’t been done before."

EXACTLY! This perfectly expresses my experiences in moving from one project to another over the years. I discover them, or they discover me. Sometimes an idea appears suddenly, seemingly out of the blue. Sometimes I think about an idea for a long time before I do anything about it, and sometimes I tackle it right away.

But there is always an element of unexpected awakening whenever an idea comes to me, a question in my mind as to what to do with it, and a sense of danger inherent in the risk I would undertake if I choose to actually address the idea. It's both exhilarating and scary, all at the same time.