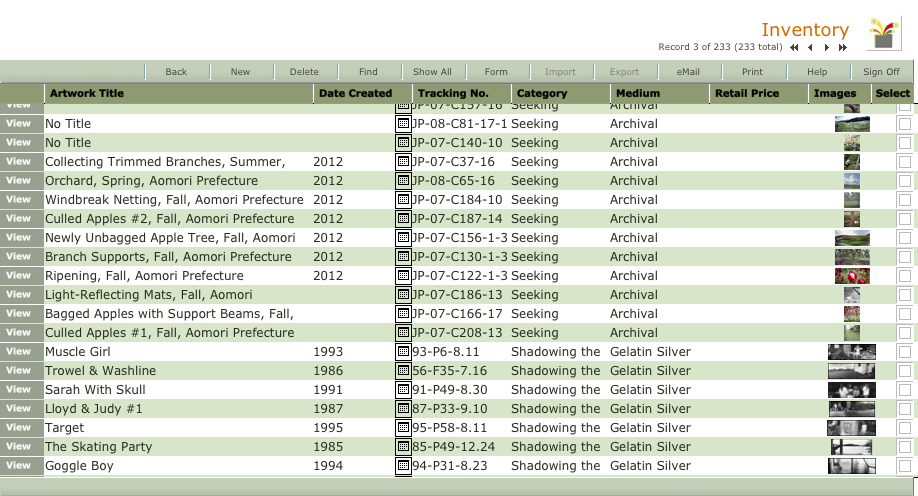

Giving titles to artwork is a challenging but rewarding part of the creative process. Although I am sure that there are many artists out there who have no problem coming up with titles, there are many others for whom it is a difficult or thankless task. I've talked with artists who hate assigning titles, and often default to "Untitled No. XXX" for their work. This is, of course, an option, but one that can work against an artist in certain respects. First, it can make it challenging to figure out which piece a potential buyer or curator is talking about unless you are an artist who has a great inventory system that allows for quickly finding your artwork in your archives. The longer you make art, the harder it may be to identify and find an untitled piece without a detailed and up-to-date inventory database. (I'm speaking from personal experience here.) Second, it can turn off certain viewers and buyers who welcome titles, as they can add meaning or provide insight into the work.

It is this value-added aspect of titling artwork that makes me work hard at coming up with an effective title. Titling forces me to engage with my art in a different way than when I am making technical or aesthetic decisions about it. I title all the artwork that I exhibit, making sure to title each body of work, as well as each piece within a series.

Sometimes titling is really hard. This was the case for the overall title of the body of work that became "Tears of Stone: World War I Remembered". I agonized over what the title should be, making long lists of potential titles, all of which were lame or awful. It wasn't until I was passing by one of my bookcases and my eye fell on a Chieftains CD titled "Tears of Stone" that I had a eureka moment. Conversely, sometimes titling is drop-dead easy. This was the case with each image in the "Tears of Stone" series. Rather than give the pictures metaphorical titles, I knew that many viewers would be very interested in the type of place and the location at which each shot was taken. The location would further indicate the scope of the war's impact the nations that fought in it. Here's an example:

On the other hand, sometimes metaphorical titles can be very effective. Here's an example from "The Primitive Streak" series that functions both literally and metaphorically, and which depicts my nieces as they neared the end of their childhood:

How do you come up with a great title for a piece of art? For me, it varies. Sometimes it comes from an external source like a discussion I have with a friend, a line in a book, newspaper, poem or song, or from listening to a podcast, as happened with the two series "The Wind Telephone" (This American Life) and "The Primitive Streak" (Radiolab). Sometimes a title is suggested by the artwork itself as I work on it. Using a thesaurus can be enormously helpful. I now keep an ongoing list of potential titles, knowing that I may never create a piece that matches up to one of those titles.

The main criteria I use for judging whether a title is effective or notis, "Does it add something to the experience of looking at the art without explaining too much?"

There really isn't one defining formula for creating successful titles for your artwork. Here are three different blogs that make excellent suggestions:

http://www.nicholaswilton.com/2014/08/06/how-to-title-your-art-so-it-sells/