My last post was inspired by a recent New York Times article about Cindy Sherman's latest body of work. In it, she presents herself in the style of old Hollywood screen goddesses who are past their prime. Rather than looking sadly like they are trying to still look like their younger selves, the women that Sherman portrays have a certain dignity to them. They look like they are older. They look like they have lived a life.

Sherman states that this work, which came after a 5-year hiatus, was the result of she herself getting older and trying to come to terms with it. She says, “I, as an older woman, am struggling with the idea of being an older woman.” And apparently she is using this new series to try to figure it out.

Sherman is now 62, an age which for many is an in-between state — not quite still middle-aged, but not yet old-old. As author Gerald Marzaroti recently wrote of people that age: "You are milling in the anteroom of the aged." The fact that Sherman is professing that this series of pictures is more autobiographically based than her prior work is really interesting to me, as is the fact that her age is a driving force in making it.

Numerous photographers have used aging as a foundation for their work- Anne Noggle and Lucy Hilmer are two who leap immediately to mind—and I, too, find myself very consciously exploring it in my own work at the moment.

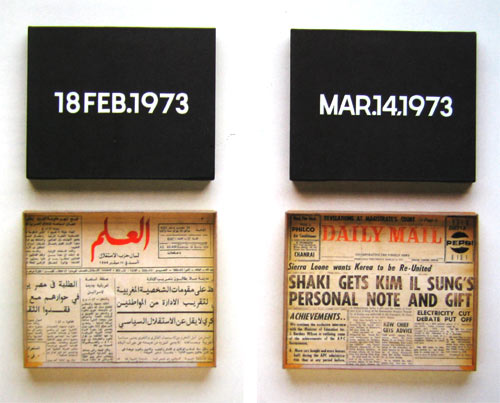

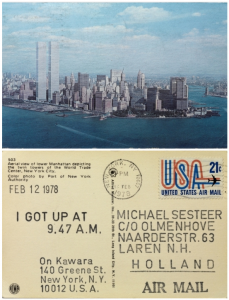

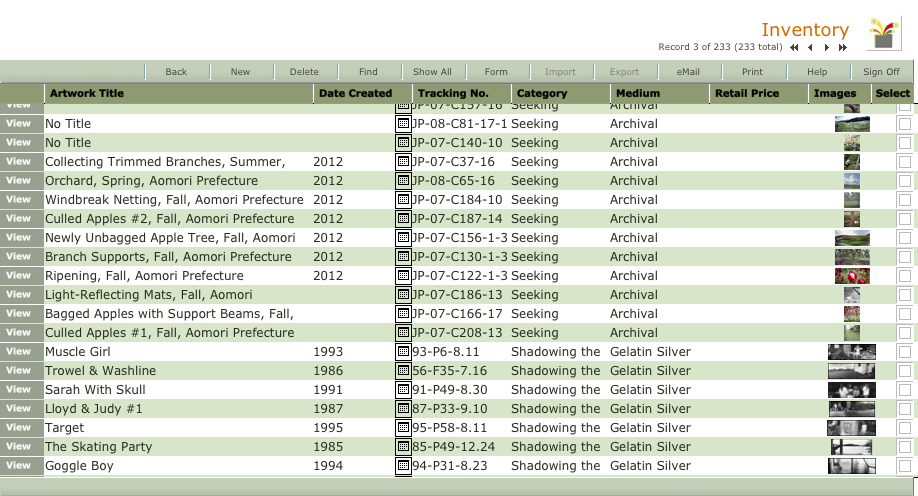

I have always been interested in the process and effects of aging. For the “Shadowing the Gene Pool” series, I photographed young children and very old adults, marveling in their similarities and differences. I did the same in the “Birth & Death” series. In my current work, I am looking at my own body, how I am aging, what I think about it, and how I see myself as I age, in addition to looking at how others age. While it is not the only issue that my new work tackles, it is a big part of it.

New York Times columnist David Brooks wrote a column back in March that speaks to how being older can enrich one’s work. Here is an excerpt:

“…(People are) less likely by middle age to be blinded by ego, more likely to know what it is they actually desire, more likely to get out of their own way, and maybe a little less likely…to care about what other people think.

…They achieve a kind of tranquility, not because they’ve decided to do nothing, but because they’ve achieved focus and purity of will. They have enough self-confidence, and impatience, to say no to some things so they can say yes to others.

From this perspective, middle age is kind of inspiring. Many of life’s possibilities are now closed, but limitation is often liberating. The remaining possibilities can be seized more bravely, and lived more deeply.”